Haydn is most famous for his later London symphonies and his earlier works, written while he was court composer at Esterhazy, are often neglected. Written for a tiny audience that was often outnumbered by the orchestra, these early symphonies allowed Haydn to experiment in a variety of ways. It is apt therefore that in the chapter “the Subtlety Hunter” Poolo pretends to be blind and deaf so that he can better understand the world, while all the time listening to Haydn’s 22nd symphony, where the opening movement uses the French horn to pose a series of musical questions that are said to be Haydn’s’ attempt to represent the unheeded calls of God to the unrepentant sinner to reform or change their views on life. As Schwartz the author of this remarkable image states

Extremely interesting things, you can only find out if you pretend to be asleep, hide behind dark glasses and show no signs of hearing anything else. its only during those long hours, when everyone is waiting for you to wake up, that you can pick up on all the subtleties, even if people can never get out of waving behind their backs and whispering.

It also provides an apt analogy for Romania and its literature which like Haydn’s early work is often unknown or neglected in the English-speaking world. In preparation for this review the author went to a large library where he was unable to find a book about Romanian literature, and then turned to its history. After going through the various countries and regions eventually he found a single book, filed under “other European countries”, called the “New Rumania” which the library had received on the 31st of January 1968, and which had remained there since unborrowed and unread.

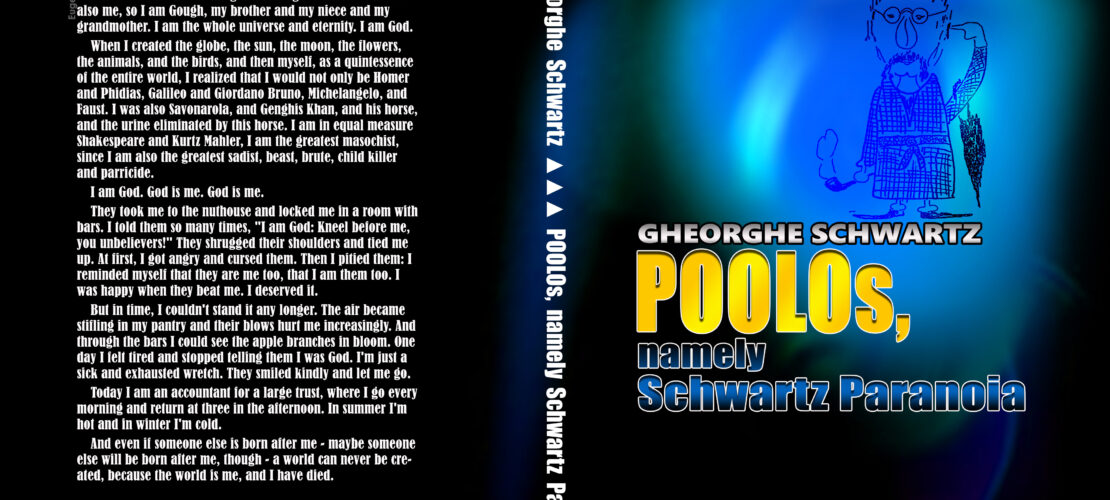

Therefore, Gheorghe Schwartz’ “Poolos” is a welcome addition to Romanian literature that has been translated into English. A satire, written in deliberate emulation of Rabelais, Schwartz uses the fantastical characters of Gough and Finch to explore the absurdity of society and this translation provides an English-speaking audience with a work that is not only part of the European mainstream literature, but which provides an insight into post-Communist Romania and the more Grotesque elements of its society.

Take for example the chapter “the Door man” where Gough gets a job at his local town hall as a porter, and then stops not only members of the public from entering but goes on the make sure that none of the staff can enter as well, reaching the point where even the chief cannot enter the building as he does not have a certificate to say he is the chief. The staff are unable use force and cannot enter the building as they cannot present a certificate. The problem is solved by them asking Gough to present a certificate himself, with his signature date and stamp confirming that he was still a doorman, which of course he cannot do as there is nobody to process the certificate for him, Gough must leave the job.

To the English-speaking reader ignorant of Romanian society such a Grotesque element is too farcical to be believable. It is only to those who have any experience of Romanian bureaucracy, especially at the time of the books original publication, that you realise that for Romanians such grotesque characters are a reality that have to be negotiated on a daily basis, and its takes an outsider a while to realise that “portarul” wield such immense indirect power that even senior officials are wary of them, but such fearsome characters are often defeated and rendered impotent by their own adherence to rules.

Yet as Schwartz’s work also speaks to a wider Pan European experience since 1990. In the chapter “the Glazier” Gough looks out the window expecting to see the old fish market and instead sees that it has been replaced by the new building of the Bank of Atlantis, gleaming glass and concrete surrounded by old houses, and reflects the rapid physical changes to cities throughout Europe that is also reflected in an emerging society where people with Irish accents have surnames like Rostas, Necula or Popescu and struggle to answer simple questions in the language of their parents. As with Rabelais depiction of the changes brought to his society brought about by the invention of the printing press and reformation and the disorienting effect that it had on people, Schwartz is similarly able to lampoon a society in transition with precision and wit.

Take for example the chapter “the Mysteries of the Congress of Carthage” where Gough in Dido like fashion provides us with the prophesy that society is changeable and that.

Here, where before our grandparents grandparents were born, the great pharaohs reigned, where we and our children now live, until the Romans come and kill them, here on this place, Carthage will burn and on its ashes the Romans will stand and die too, and the Arabs will come, and the Moors and the jews, then the Spanish and the French, and others and others will come. And the English will come and the Germans and the English again”.

Which is rapidly lampooned by Finch proving that Carthage would be destroyed by the Filipino’s and later become the capital of Denmark.

Schwartz as with Rabelais before him rightly confirms that only satire can explain the absurdities that confront us when society is rapidly changing and transforming. Until I picked up a book and read a book that had laid unread for decades, I was unaware that the dominant political ideologies in Ireland and Romanian in the early 20th century, “Prin noi înșine” and “Sinn Fein” have the exact same translation in English. Schwartz’ work having now found its way to a wider audience that will hopefully appreciate its subtle use of word play and imagery.